HOSTED BY: https://1airtravel.com

TODAY'S READ

*Originally posted on travelradar.aero - the leading aviation news source*

If you are a regular air traveller or perhaps an AvGeek, you may have asked, how do pilots find their way in the sky? There have been talks of pilot shortages and strikes, and if you are an avid follower of Travel Radar, you would have learnt why there are two pilots on the flight deck. Regular air travellers may well know that flying a plane is not quite the same as driving a car, handling a locomotive, sailing a boat, or paddling a canoe. It is a lot more complex than all of these. While driving a car, you can find your way from one point to another by knowing where to turn on the road, or guided by a map or memory, but at 36,000ft it is not quite the same!

In the past few years, the Global Positioning System (GPS) has become the primary way pilots navigate the sky. However, simple as that may sound, we need more than that to satisfy our curiosity because it raises more questions. Such questions as how did pilots find their way in the sky before GPS? Which navigation system did they use? Are those navigation systems still in use today? Answering these three questions will satisfy our curiosity and give us more knowledge. Hence, we dug deeper to find satisfactory answers to the questions above.

The Early Days of Aviation

In the early days of aviation, pilots found their way through the sky by looking out the window for natural landmarks like hills, towns, lakes, or church steeples, just as they did on the ground. Celestial navigation, which is the method of finding their way in the sky by observing celestial bodies like the sun, moon, and stars, was also an option for pilots.

The US airmail carriers started flying in 1920, and pilots could navigate the airmail carriers at night by looking out for strategically placed bonfires on the ground. In the day, large concrete arrows were placed by people on the earth, they were visible to pilots in the air, and they pointed in the direction.

Pilots used these bonfires and arrows alongside pilotage and dead reckoning to navigate their aircraft. However, there have been more advanced radio navigation systems in the past few years. Introducing radio navigation aids such as VOR and improvements in flight instruments means that pilots can fly without visual references pointing the way on the ground.

The advancement of the modern navigation tools now available to the pilot means that pilots can navigate at higher altitudes and through clouds without peeping out the window for landmarks or strategically positioned arrows or bonfires pointing the way. With the introduction of GPS, navigation has been made easier and more efficient for pilots.

Pilotage

Bonfires were used to guide pilots in the past | © Wikimedia Commons

Pilotage is perhaps the first aircraft navigation skill pilots must learn in flight school. Back in the day, it was easy and foolproof. It was the most basic skill and means of navigating the sky under visual flight rules (or VFR). Without the GPS of today or any form of radio aid which are available to pilots in recent years, early pilots found their way in the sky just like they did on the ground, using a compass, and looking out for visual landmarks like a church steeple, hills, or lakes.

However, pilotage’s pitfall is that it forces pilots to take their eyes off the horizon and the instruments in their cockpits. And using pilotage as the sole source of navigating the sky wasn’t entirely consistent, safe, or trustworthy. The more time the pilot spends looking inside the cockpit, the less situational awareness they have of what is outside the window.

The rules of VFR imply that pilots must see and avoid, maintain a certain distance from other aircraft, and not fly through or over cloud formation.

In simple terms, pilotage means that pilots look out the window to spot visual landmarks like mountains, towers, cities, lakes, and rivers and compare what they can see with the printed sectional chart available to them in the cockpit.

Even at night, pilotage worked for pilots; pilots just looked out for highways, city lights, and airports.

Although in the early days of aviation, pilotage was easy, there are more efficient means for pilots to find their way in the sky. It is also limited to VFR weather conditions. Hence, it only applies when the pilot has the ground in sight. While pilotage is still required for maritime pilots, the recent technological surge ensures that it is optional in the aviation industry.

Don’t worry. The next time you see your pilot looking out the window, he may not be looking out for natural or visual landmarks. He has enough aircraft navigation instruments in his cockpit to find his way in the sky. However, the system is still in use today.

Dead Reckoning

The proposed rule was drawn up with the safety of pilots as the main focus. | © Unifor

As aviation advanced, more navigation aids were produced, and pilots found new means of finding their way around the sky. One such means was dead reckoning. Dead reckoning is simply the process of navigating by calculating distance and time based on the airplane’s ground speed.

Like pilotage, dead reckoning is still in use but demands preparation. Unlike pilotage, where pilots look out for landmarks, dead reckoning requires that pilots be familiar with how much is involved when flying from one point to another on the earth if he travels at a specific airspeed. This enables the pilot to match the landmark with the map.

Navigating the sky by dead reckoning requires proper airspeed calculations, wind direction, wind speed, and other factors.

Non-directional beacons (NDBS)

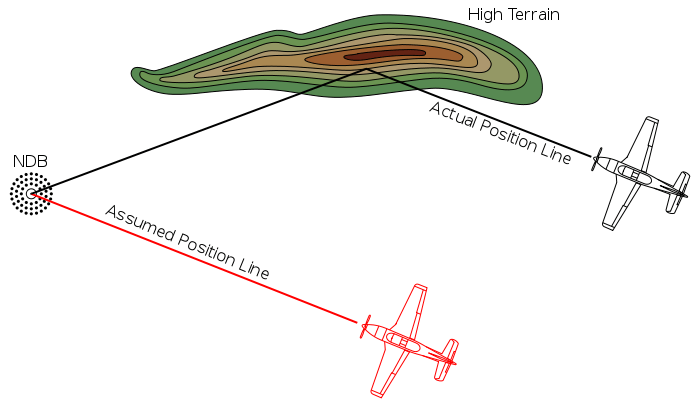

A diagram showing the “Terrain Effect”. High ground reflects a non-directional beacon’s (NDB) signal, causing the position of the aeroplane to be incorrectly determined (red line and aeroplane).

NDBS was one of the first navigation systems and is still available to the pilot. NDBS are radio beacons that transmit radio waves to an aircraft’s receiver or antenna. With the Automatic Direction Finder (ADF), NDBS helps interpret signals. The ADF shows where the aircraft is located in relation to the beacon. With the information, the pilot could direct the airplane to the source of the signal.

The pilot must also tune in to the next beacon on the route and repeat the process until it is time to land the aircraft.

NDBS and AFD were more reliable and efficient than attempting to navigate the aircraft with visual landmarks. However, the signals were only sometimes trustworthy. Travelling at sunrise, sunset, or during thunderstorms could interfere with signals. Again, mountainous terrains could produce false signals.

Most worrying was the airplane’s antenna producing erroneous readings while in bank turn, referred to as bank error.

Non-directional beacon at Gjoa Haven Airport (YHK), Nunavut, Canada. |© Gordon Leggett

VORS

The advent of radio navigation made it possible for pilots to fly more efficiently and safely in good weather or adverse weather conditions. Radio navigation enables pilots to fly instrument flight rules (IFR), initially known as blind flying. A pilot that wants to navigate an aircraft under IFR must obtain an instrument rating from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Radio navigation aids are generally known as NAVAIDS.

VOR is an acronym for VHF (very high-frequency) Omnidirectional (Radio) Range and is used frequently by pilots today. The system includes:

A ground stationAn antenna on the aircraftAn instrument in the cockpit that displays and interprets the aircraft’s position in relation to the signals radiated from the VOR station on the groundA VOR emits two kinds of signals: simultaneously in all directions-directional signal (omnidirectional) and a rotating signal which sweeps in circles. It is essential to mention that the frequency of these signals is high. Hence, they cannot be picked up by transistors, radio, or car antenna.

While VOR is a more advanced technology than pilotage and dead reckoning, it is less accurate and easy to use than GPS. Although it does not involve satellites, it is trustworthy and used by many pilots as a backup to GPS.

Wilcox 585B VHS omnidirectional range transmitter. |© Wikimedia Commons

Global Positioning System (GPS)

GPS is perhaps the most advanced technology that helps the pilot to find his way in the sky. It is the most common and accurate navigation system today and is based on precise satellite data.

First available as an individual navigation aid, most pilots are now familiar with GPS and expect it to be part of the navigation aid imbued in the cockpit.

GPS isn’t perhaps infallible; however, it is highly accurate and is not subject to atmospheric interference, antenna error, or natural features which might block or impair signals. GPS depends on 24 satellites to locate the airplane and guide it along its flight path.

GPS helps pilots to plot direction and calculate speed and position. GPS ensures that pilots can travel directly from point A to Point B rather than from VOR to VOR or via any specific route. Pilots using GPS fly more efficiently and save their airlines time and money. GPS is the most advanced flight aid available to the pilot. However, history has shown that it may not be the best in the next decades, generations, or centuries.

GPS Block II-F satellite in Earth orbit |© Wikimedia Commons

Summary

If you have ever wondered how pilots find their way around the sky, here is the answer to your question. The aviation industry is a fast-paced environment and is never static. One innovation leads to the other and then to the other. This implies that the aviation industry has experienced stable growth in technology, and there is no doubt that in the future, there could be better alternatives to even the best systems mentioned in this article.

What do you think of the navigation systems mentioned in this article? Please drop a comment.

**CONTENT ORIGINATED FROM TRAVELRADAR.AERO***https://travelradar.aero*

By: Victor UtomiTitle: Aircraft Navigation: How Do Pilots Find Their Way In The Sky?

Sourced From: travelradar.aero/how-do-pilots-find-their-way-in-the-sky/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=aircraft-navigation-how-pilots-find-their-way-the-sky

Published Date: Mon, 14 Nov 2022 22:45:09 +0000

Did you miss our previous article...

https://1airtravel.com/feature/cathay-pacific-closes-last-international-pilot-base